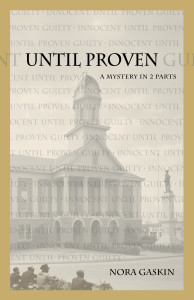

“I like to let the characters have their say, even with a plot line that involves murder and mayhem.” So says Nora Gaskin, author of Until Proven and Time of Death. In these books Gaskin explores the story of two young North Carolina women killed in their homes forty years apart. Until Proven is a fictional account of the incidents and Time of Death is a true account of the actual trial, giving readers a rare opportunity to step into the writer’s shoes as she envisions, enlarges, and recreates those horrible happenings.

“I like to let the characters have their say, even with a plot line that involves murder and mayhem.” So says Nora Gaskin, author of Until Proven and Time of Death. In these books Gaskin explores the story of two young North Carolina women killed in their homes forty years apart. Until Proven is a fictional account of the incidents and Time of Death is a true account of the actual trial, giving readers a rare opportunity to step into the writer’s shoes as she envisions, enlarges, and recreates those horrible happenings.

Gaskin also operates a publishing company, Lystra Literary Services, where she assists writers in independently bringing their books to market, marrying the best of traditional and self-publishing models. She uses her experience as an author and publisher to help writers ensure their works are developed to their full, professional potential.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Gaskin recently to learn about her books and get her thoughtful take on writing and publishing.

Drop by Lystra Literary Services to find out where you can get Gaskin’s books and learn more about their publishing and writing services.

Voicings is a series of interviews conducted by writer Tyler Johnson featuring writers, musicians, artists, and thinkers in their own words.